The key differences between CapEx and OpEx are not just accounting treatment – they define ownership, risk, and payback. CAPEX is upfront investment on the balance sheet; OPEX is recurring operating expenses on the income statement. This choice changes total cost of ownership and how fast a commercial energy storage system actually pays back.

What CAPEX covers

Capital expenditure (CAPEX) is the entry cost and refers to major purchases and long term investments in physical assets and fixed assets – such as buildings, equipment, infrastructure, and energy storage systems. These costs are classified as capex assets (capital expenses) on the balance sheet and typically depreciated over time. CapEx spending commonly includes property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), and can also cover intangible assets such as software, patents, or technology required to operate the system. Because CAPEX requires a larger upfront investment, it usually involves a longer approval process and is often financed through debt or equity.

For financial planning, companies calculate CAPEX to track investments, operational costs, and how the capex asset creates long term value beyond the current year. Typical examples of capital expenditures include purchasing land, constructing buildings, and acquiring machinery – but in commercial energy storage systems, the real CAPEX is the battery hardware, power electronics, and grid infrastructure that drives performance.

It includes batteries, inverters, housing, grid connection, engineering, and commissioning. Once paid, the system becomes your asset and sits on your balance sheet as an existing asset. From that point, depreciation starts and performance risk becomes yours.

High capital spending gives control and ownership. It also makes you responsible for maintenance, downtime, and replacement. A cheap installation with poor efficiency will always be more expensive over time than a costly one that performs well.

What OPEX really means

OPEX refers to operating expenditures: ongoing costs and recurring expenses required for day to day operations, such as maintenance, software, insurance, replacements, and electricity for charging (grid power). These operating expenses (OPEX) support immediate operational needs and are reported on the income statement (profit and loss statement), where they are typically expensed immediately and deducted from income in the year they are incurred. Compared to CAPEX, this accounting treatment offers more flexibility and makes costs easier to adjust over time.

In commercial energy storage systems, OPEX can also describe service-based models where the supplier retains ownership and charges a recurring fee for system use. For the buyer, these recurring costs behave like installments: predictable operating expenses rather than capitalised investments. OPEX may also include routine recurring expenses such as monitoring, cybersecurity, performance reporting, and utility bills related to auxiliary loads (HVAC, heating, standby consumption), which matter in cold climates.

OPEX models lower the barrier to entry and transfer part of the operational risk to the vendor. They also limit upside: you pay for performance, not ownership.

Choosing between CAPEX and OPEX

The CAPEX vs OPEX decision is a business strategy choice: ownership and upside versus flexibility and risk transfer.

CAPEX gives higher long-term profit potential and strategic independence, but ties up capital through upfront costs and makes you responsible for performance, downtime, and replacement risk.

OPEX reduces entry cost and shifts part of the risk into predictable operating expenses and recurring costs, but keeps you dependent on third-party performance and contract terms.

Hybrid structures are increasingly common in Europe: leasing, energy-as-a-service, and performance-based PPAs combine both CAPEX and OPEX logic by splitting ownership, ongoing costs, and risk allocation.

The correct model depends on liquidity, credit policy, tax treatment preferences, and your ability to manage the asset technically over its full life.

The real payback window and drivers in the commercial batteries

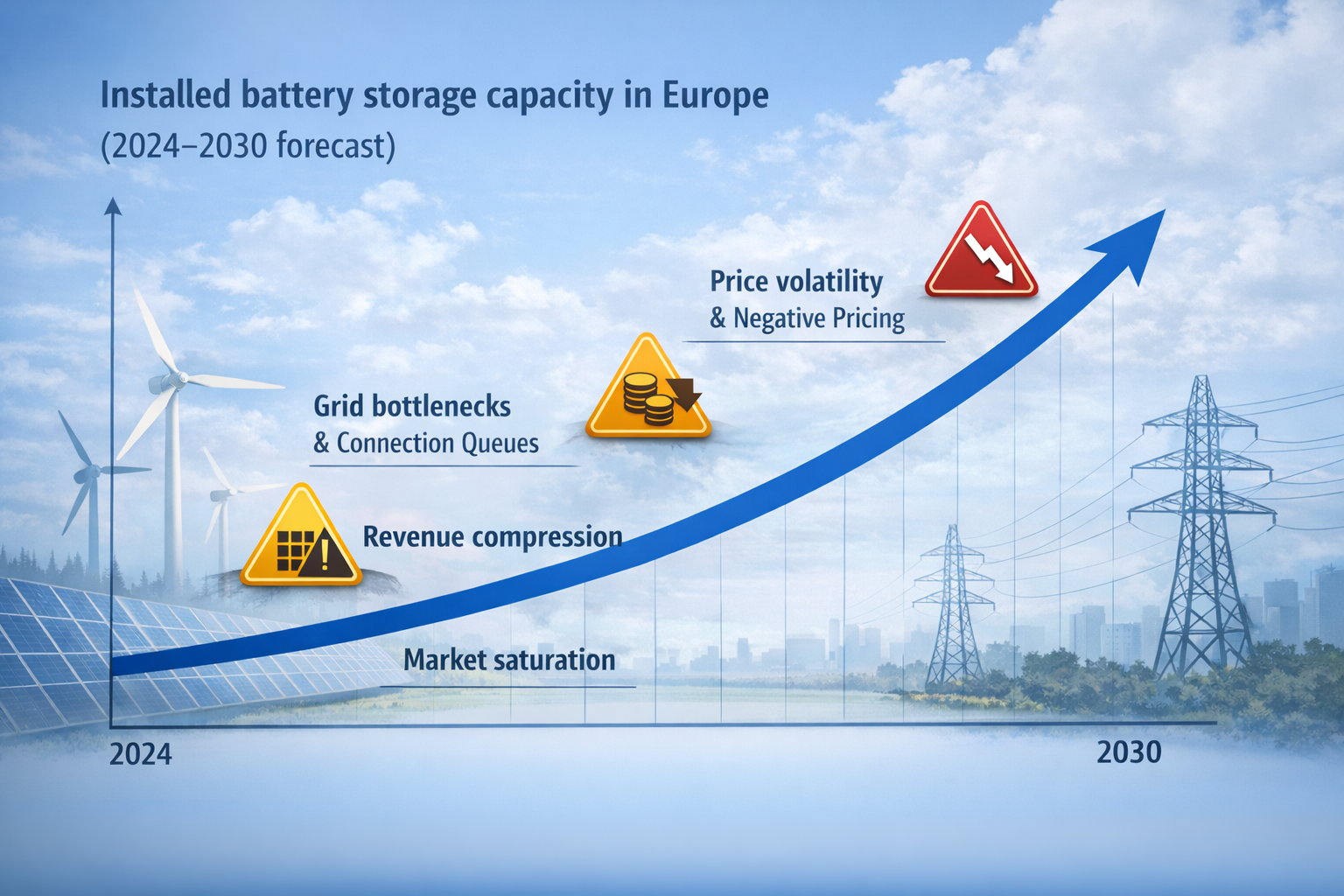

Independent project benchmarks and industry analyses show a relatively consistent payback range for commercial and industrial energy storage projects. In practice, payback is often 7–9 years on average, 5–6 years in strong market conditions with stacked value streams, and can extend to 10–12 years for conservative or underutilised systems.

Common drivers behind faster payback include multiple revenue streams (price arbitrage + peak shaving + grid services), high utilisation rates, and strong spreads in electricity markets. Major energy agencies and industry research firms consistently highlight these factors as the core economics behind battery storage performance.

What shortens payback

High demand charges or wide time-of-use spreads in electricity markets.

Consistent daily cycling and accurate dispatch control (EMS optimisation).

Integration with on-site solar panels or other renewable energy generation to increase self-consumption and reduce grid power purchases.

Efficient maintenance discipline, performance monitoring, and fast fault response to minimise downtime.

Stacking multiple value streams: peak shaving, grid services, and frequency response.

In practice, commercial battery energy storage and industrial energy storage systems shorten payback when they deliver measurable cost savings: reducing electricity costs, stabilising energy usage, and ensuring uninterrupted operations for commercial facilities and manufacturing facilities. The best commercial energy storage solutions combine strong technical performance with reliable power delivery and a dispatch strategy that monetises stored energy across multiple use cases.

What extends payback

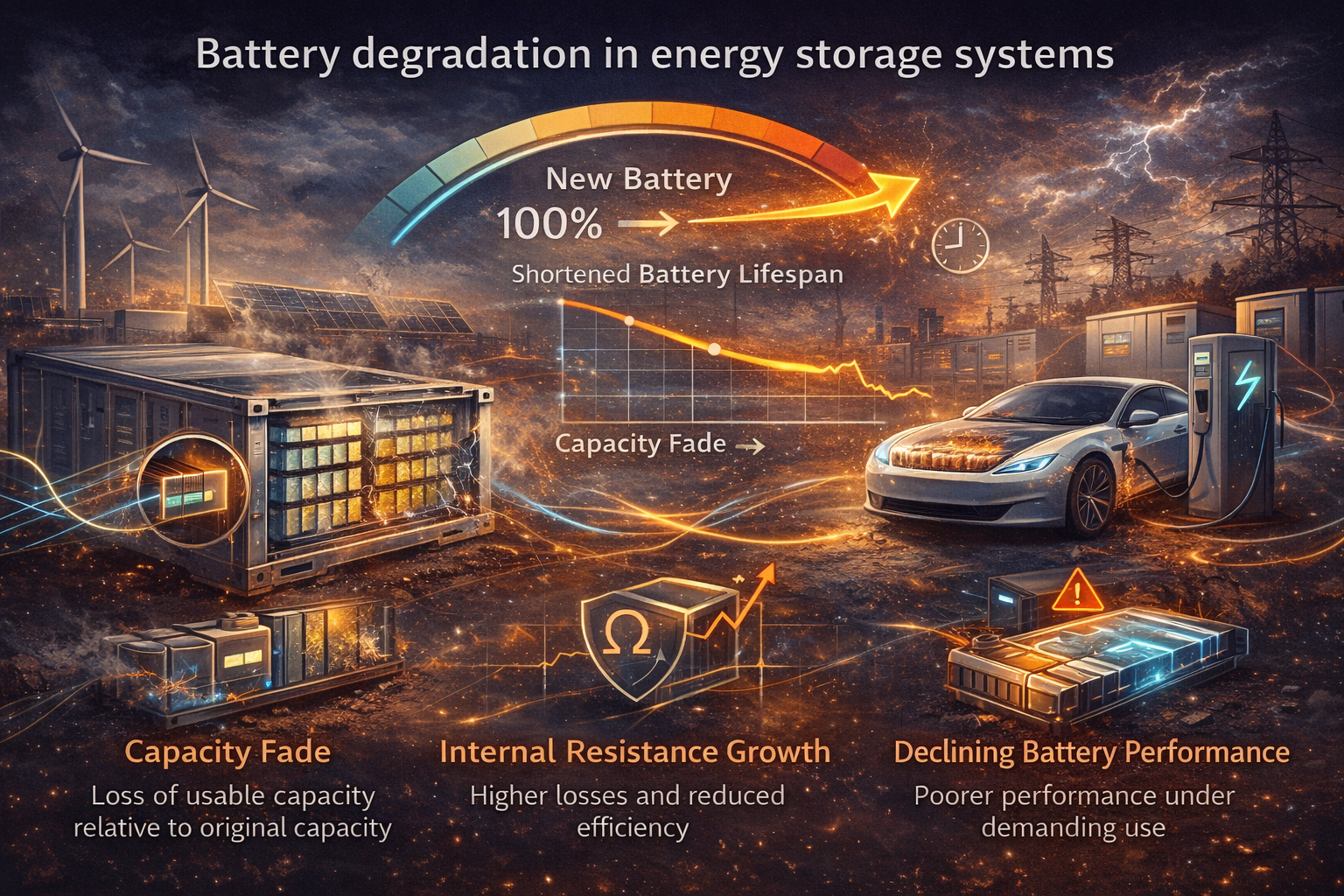

Idle or oversized systems that cannot cycle consistently (low utilisation rate).

Weak maintenance discipline, slow fault response, and poor performance monitoring.

Faster-than-expected degradation, reduced usable capacity, and downtime that cuts revenue.

Hidden service costs in OPEX contracts (software fees, reporting, spare parts) or weak warranties that shift replacement risk to the buyer.

Unstable regulation, tariff volatility, or reduced access to grid services and demand response programs.

Deciding the structure

If your organisation has capital and operational competence, full ownership under CAPEX typically delivers higher lifetime profit, better total cost of ownership, and strategic independence.

If liquidity or in-house expertise are limited, service-based OPEX models convert the project into predictable operating expenses with reduced exposure to technical risk and downtime.

Hybrid agreements (leasing, energy-as-a-service, performance-based contracts) split both risk and benefit and are increasingly common across commercial energy storage systems.

The right choice is the one that aligns financial strategy, risk allocation, and technical capacity over the full asset life.

The payback rule

Projects recovering cost within six years are financially strong.

Between six and ten years, they are acceptable – but only with disciplined operation, accurate dispatch, and tight performance control.

Beyond ten years, they become speculative and heavily dependent on future regulation, tariffs, or subsidies.

Return is not defined by installation cost alone, but by how efficiently each euro invested converts into measurable savings, revenue, and total cost of ownership value across the system’s life.

Summary

Capital expenditure defines ownership.

Operational expenditure defines continuity.

The real payback of a commercial energy storage system appears when CAPEX and OPEX are balanced, when invested capital and operational performance support each other instead of competing. The payback period is not just a spreadsheet output; it is total cost of ownership translated into daily operating discipline.

Energy storage is not equipment. It is a financial mechanism that earns value only when managed with precision.

Related Products from Aema ESS

Explore Aema ESS energy storage solutions for backup power, grid support, and renewable energy integration.

Featured systems:

Contact us today to receive a tailored offer for your upcoming project.