Introduction

Battery degradation is an inevitable process in energy storage systems. It is the central economic parameter that determines whether a project remains profitable after years of operation. For both grid-scale storage and stationary energy storage, degradation determines how quickly an asset loses energy storage capacity, how much power it can still deliver at peak demand, and how long operators can avoid battery replacement. The same topic dominates the EV world: ev batteries in electric vehicles degrade through similar physical and electrochemical mechanisms, and the market has learned that battery health is not only a technical number but a financial outcome.

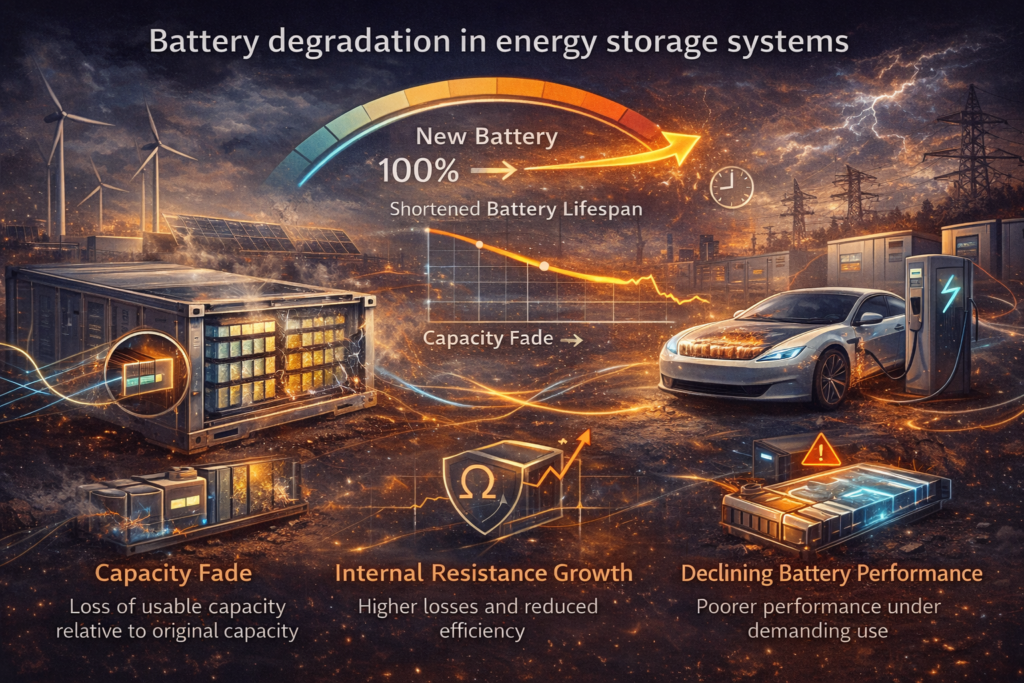

In practice, when we say batteries degrade, we usually refer to three measurable effects: capacity fade (loss of usable capacity relative to original capacity), internal resistance growth (higher losses and reduced efficiency), and declining battery performance under demanding use. Together, these factors determine battery life, battery lifespan, and ultimately battery longevity.

What battery degradation actually means

Battery degradation is often described as a slow decline, but in real operations it behaves like a curve with multiple drivers. A lithium-based storage asset can look stable for a period and then show faster performance decline when thermal conditions, charging behavior, or cycling intensity change. This is why the industry tracks not only capacity but also battery health management, often represented by state of health metrics. At the system level, battery degradation is visible through reduced discharge duration, lower sustained power output, increased heat generation, and a noticeable gap between nameplate rating and real deliverable energy.

The most important idea for project owners is this: degradation is not only driven by time. It is driven by battery operation: how many discharging cycles the asset completes, how deep those cycles are, whether operators frequently push fast charging, and whether the system experiences temperature extremes.

Two mechanisms behind degradation: aging vs cycling

Nearly all degradation behavior in lithium storage can be separated into two categories.

The first is calendar aging (also called calendar degradation): degradation that happens simply because time passes, even if the battery is not used heavily. This type is strongly influenced by storage conditions, especially operating temperatures, moderate temperatures, and the state of charge the battery is held at for long periods. Calendar aging is where you see the influence of chemical reactions progressing slowly inside the cell, such as electrolyte breakdown and growth of interfacial layers.

The second is cycling-related degradation: battery wear caused by repeated charge and discharge. Each cycle creates mechanical and chemical stress, and the intensity depends on deep discharges, voltage range, and how aggressively the battery is charged or discharged. Cycling degradation is why ev battery degradation becomes visible faster in some fleets than others, the same chemistry behaves differently under different driving habits, fast charging frequency, and climate conditions.

In an energy storage system, these two mechanisms overlap. A project can be lightly cycled but stored in hot conditions, producing strong calendar aging. Or it can be stored in stable temperature but cycle aggressively to maximize revenue, producing faster cycle-driven degradation. The final degradation rate is the combined result.

What happens inside a battery cell during battery degradation

When we discuss battery degradation, we usually describe what is visible at system level: capacity fade, reduced battery capacity, and declining battery performance. To understand why these metrics change, it helps to look at what happens inside the battery cell, because both external factors (temperature, charging behavior, cycling strategy) and internal electrochemistry determine long-term outcomes.

Inside lithium ion batteries, degradation is driven by several parallel processes that reduce the amount of usable lithium and worsen charge transport. The protective SEI layer on the anode grows over time and consumes active lithium, while the electrolyte slowly breaks down, especially under heat. This process is a major contributor to battery aging and explains why the battery state (especially high SOC) matters even when the system is not actively cycling. Repeated discharging processes also cause mechanical stress: electrode materials expand and contract, microcracks form, and parts of the active material lose electrical contact, accelerating capacity fade and lowering usable energy.

Under stressful charging conditions, particularly fast charging (or high-current charging in cold weather), lithium plating can occur, increasing losses and accelerating degradation. While slow charging can reduce plating risk, it does not eliminate calendar degradation if the battery remains stored at high SOC and elevated temperatures. At pack level, these mechanisms accumulate across the whole battery pack, reducing capacity over time even if the unit continues to operate normally.

A key point is that lithium-ion behavior differs from other chemistries. For example, lead acid batteries often have a low self discharge rate advantage and different aging characteristics, but they also degrade through distinct mechanisms such as sulfation and active material shedding. In lithium ion systems, however, SEI growth, electrolyte decomposition, structural wear, and plating together explain why degradation depends not only on age, but on various factors in real operation, including temperature extremes, cycling intensity, and charging behavior in modern energy storage deployments.

Why energy storage systems degrade differently than electric car batteries

Both electric car batteries and stationary systems use similar lithium ion batteries, but the duty cycle differs. EVs experience fluctuating power spikes, regeneration, varied temperature exposure, and behavioral patterns. Energy storage systems, however, often operate in predictable regimes: daily cycling, scheduled dispatch, and controlled charging behavior.

That predictability is an advantage. Stationary projects can engineer degradation down using stable thermal management, controlled depth-of-discharge windows, and optimized dispatch strategies. But they also face risks EVs avoid: storage projects can run near-constant cycling in certain markets, which increases cumulative wear. In frequency response and arbitrage strategies, the system might execute many micro-cycles per day, raising the number of effective cycles even if each cycle is shallow.

In other words, degradation in energy storage systems is not necessarily “slower” than EVs. It depends on the market, dispatch strategy, and the technical configuration.

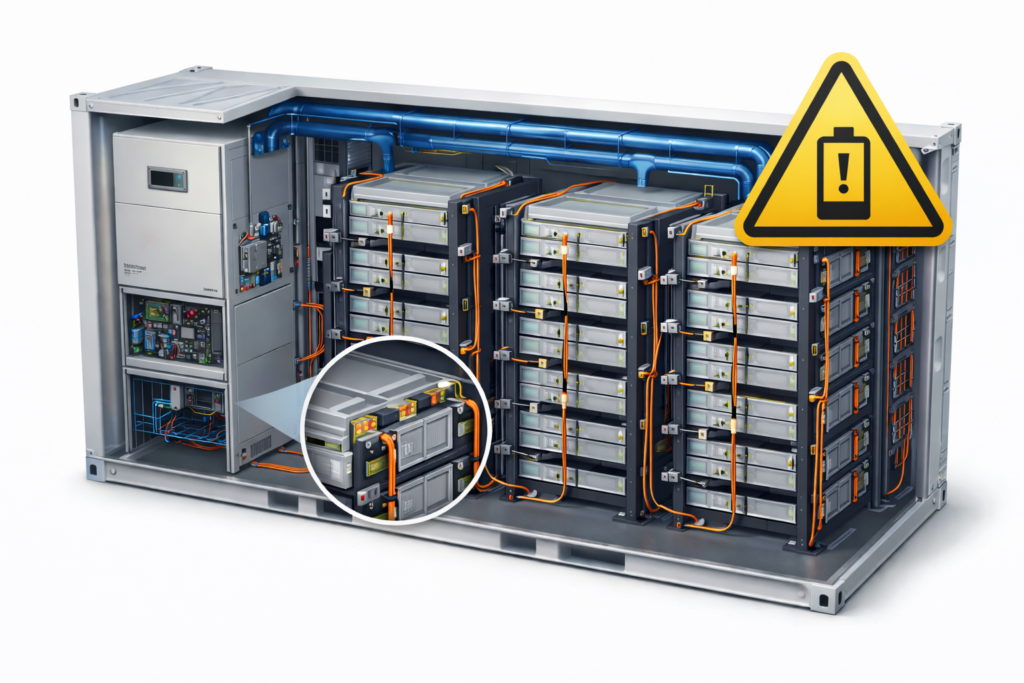

Battery management systems as the control layer for battery health

The practical tool for controlling degradation is the battery management systems layer. A modern energy storage project relies on battery management systems bms logic to monitor cell voltages, temperature distribution, current flow, and safety thresholds. BMS is the reason the system can deliver power efficiently while limiting risk.

Good control algorithms reduce degradation by keeping the cell within an optimal temperature range, limiting aggressive charging behavior, and preventing unsafe conditions that accelerate wear. These systems provide feedback and diagnostics that help operators adjust dispatch behavior before degradation becomes irreversible. In operational terms, BMS is not just safety. It is a battery health management system.

In well-designed systems, BMS and thermal management systems work together: cooling, airflow, and pack design keep temperature within stable operating ranges, preventing localized hot spots that degrade cells unevenly.

Capacity fade: why energy storage capacity declines over time

The most visible degradation metric is capacity loss. Capacity fade means the battery cannot store as much energy as before, reducing both operating flexibility and revenue. When capacity declines, the system delivers less useful energy per cycle and may miss performance commitments.

Capacity fade is not uniform across all projects. It depends on cell chemistry, cycling profile, and temperature. LFP and NMC chemistries degrade differently and respond differently to fast charging. Higher average temperature and higher average SOC typically push faster decline. In stationary projects, avoiding extreme operational patterns is often the best way to preserve long-term energy storage capacity.

Internal resistance: the hidden degradation that kills performance

If capacity fade is visible, internal resistance is the silent killer. As internal resistance rises, the battery loses efficiency: more energy is wasted as heat, power output becomes harder to sustain, and thermal risk increases. This affects battery efficiency, and it can reduce the system’s ability to deliver peak power even when capacity still looks acceptable.

Rising internal resistance is also why aged systems can feel “weak” even if their measured capacity seems fine. Their battery’s ability to deliver high power drops. In many commercial contracts, the performance KPI is not only energy but also power output under defined conditions, meaning internal resistance matters for warranty claims.

Degradation models and how operators forecast lifetime

Because degradation is inevitable, the industry relies on degradation models to forecast remaining life and plan warranty or replacement schedules. These models estimate degradation rates from calendar aging and cycling exposure, using operating temperature profiles and usage intensity.

For project owners, degradation modelling is not academic. It defines contract terms, grid service availability, and replacement planning. It also determines the difference between “paper performance” and real financial outcome.

Battery warranty, replacement, and second-life options

Most large projects include a battery warranty that specifies acceptable capacity loss thresholds and performance commitments over time. When those thresholds are exceeded, owners may consider battery replacement, partial repowering, or new pack insertion.

Before replacement, some assets can be repurposed into battery second life applications, where lower-performance batteries can still serve in less demanding roles. In EV markets, this concept is often discussed as reusing EV packs for stationary energy storage, extending total value extracted from batteries.

At end of life, recycling becomes the final stage. Projects increasingly aim to recover valuable materials, since lithium, nickel, cobalt, and other valuable components are too important to waste. Recycling is also part of the long-term sustainability picture.

Practical steps to extend battery life in energy storage

Operators can meaningfully extend battery life without sacrificing all revenue. The most effective approach is strategic operating discipline: keep cycling within controlled depth-of-discharge limits, avoid extended high SOC exposure, maintain stable temperatures, and prevent repetitive high-stress charging behavior. Systems perform best when the operating environment is stable and the software control layer actively manages risk.

In short: degradation is not random. It is manageable — but only if the operating strategy is designed with battery health in mind.

Future trends: why degradation management is becoming a competitive edge

As the market expands, degradation control is becoming a differentiator. In modern evs, battery performance depends on how software manages charging windows, thermal conditions, and fast charging events. In stationary energy storage, the same trend applies: the winners will be projects that deliver high utilisation without destroying their cells.

New batteries continue to improve in chemistry stability and safety architecture, but degradation will remain a critical role in investment decisions. The reason is simple: the best project is not the system that looks perfect on day one, but the one that still delivers reliable energy and power after years of real operation.

Related Products from Aema ESS

Explore Aema ESS energy storage solutions for backup power, grid support, and renewable energy integration.

Featured systems:

Contact us today to receive a tailored offer for your upcoming project.