Introduction

A BESS is the physical asset, but the EMS is what turns that asset into profit. The energy management system controls dispatch, charging and discharging processes, and market participation, which means it effectively controls cash flow. Two identical battery storage systems can generate completely different returns depending on the EMS, the way it schedules energy flow, how it stacks revenue streams, and how it reacts to the market prices, grid constraints, and state of charge.

That is why the “chicken or egg” question is real. The ESS defines technical capability: battery capacity, power output, and operating limits. The EMS defines monetisation: energy arbitrage, ancillary services, and grid services. If the EMS is weak, the project becomes a commodity and margins compress. If the EMS is aggressive but poorly disciplined, it can accelerate degradation and push the asset into warranty risk.

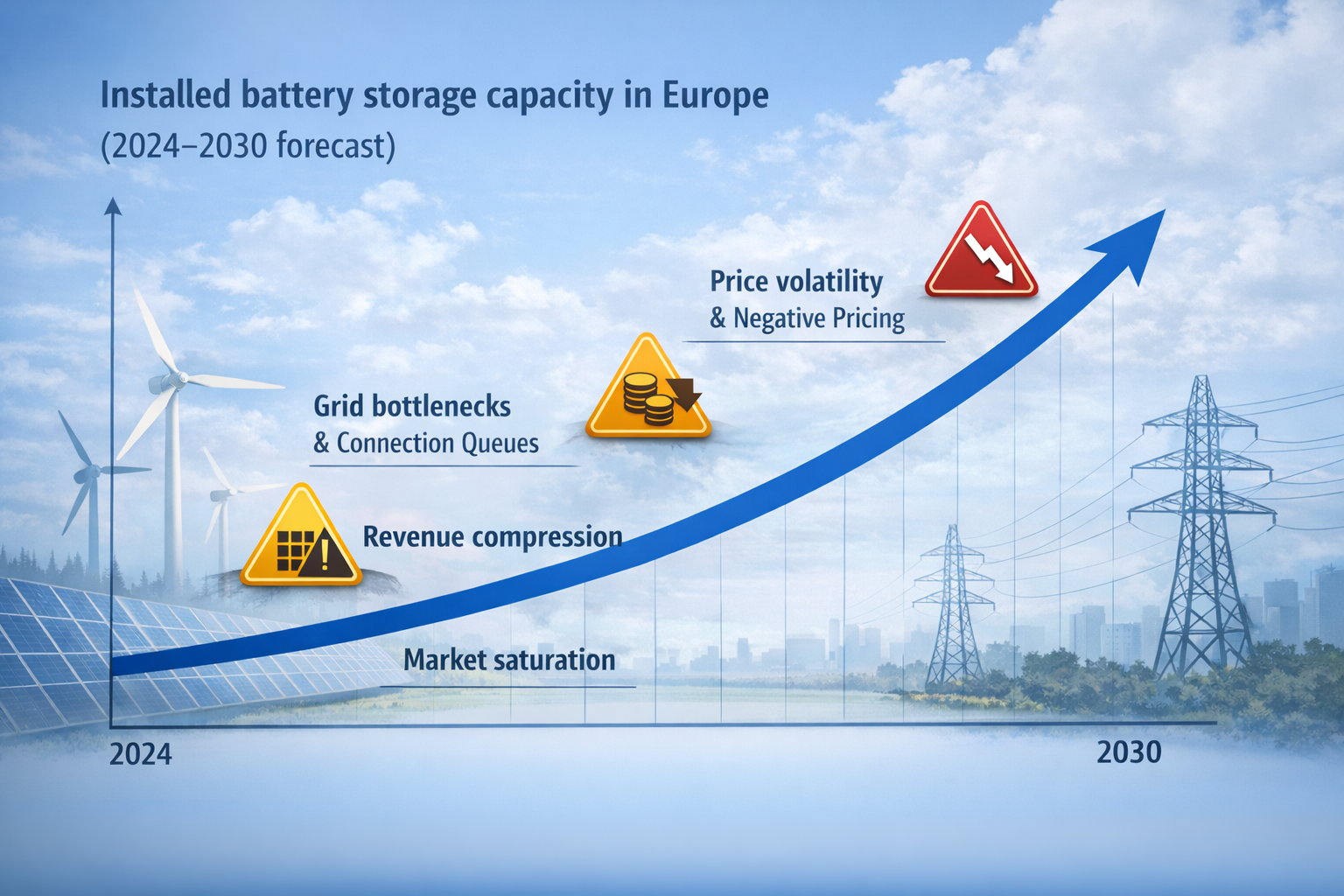

In saturated markets, this difference becomes brutal. As more storage projects compete for the same revenue pools, the edge shifts away from hardware and toward the control system. EMS is not just a software. It is the operational layer that decides who earns, who loses, and who ends up carrying the risk.

What does energy management system actually control in a BESS

An EMS system is not “monitoring software”, it is the control layer that decides how the battery energy storage system behaves minute by minute. It uses real time data from the power grid interface, site meters, inverter telemetry, and market feeds to run smart scheduling. The EMS plays the central role in optimising operations: choosing when to charge in off peak hours, when to discharge into peak demand, and when to reserve headroom for grid services like frequency regulation. This is the difference between a system that simply stores energy and a system that extracts value from energy arbitrage, ancillary services, and grid interactions.

A strong EMS logic is specifically designed to translate market volatility into dispatch decisions in an effective manner. It uses forecasting, predictive analytics, and data analysis to react to changing energy consumption and energy usage patterns. Even small improvements in data accuracy can impact system performance because the EMS decides power output targets, ramping profiles, and reserve margins under constraints. In short, the EMS controls cashflow by controlling energy flow, and it controls operational efficiency by deciding when cycling is worth it.

What the ESS controls and why BESS EMS cannot override physics

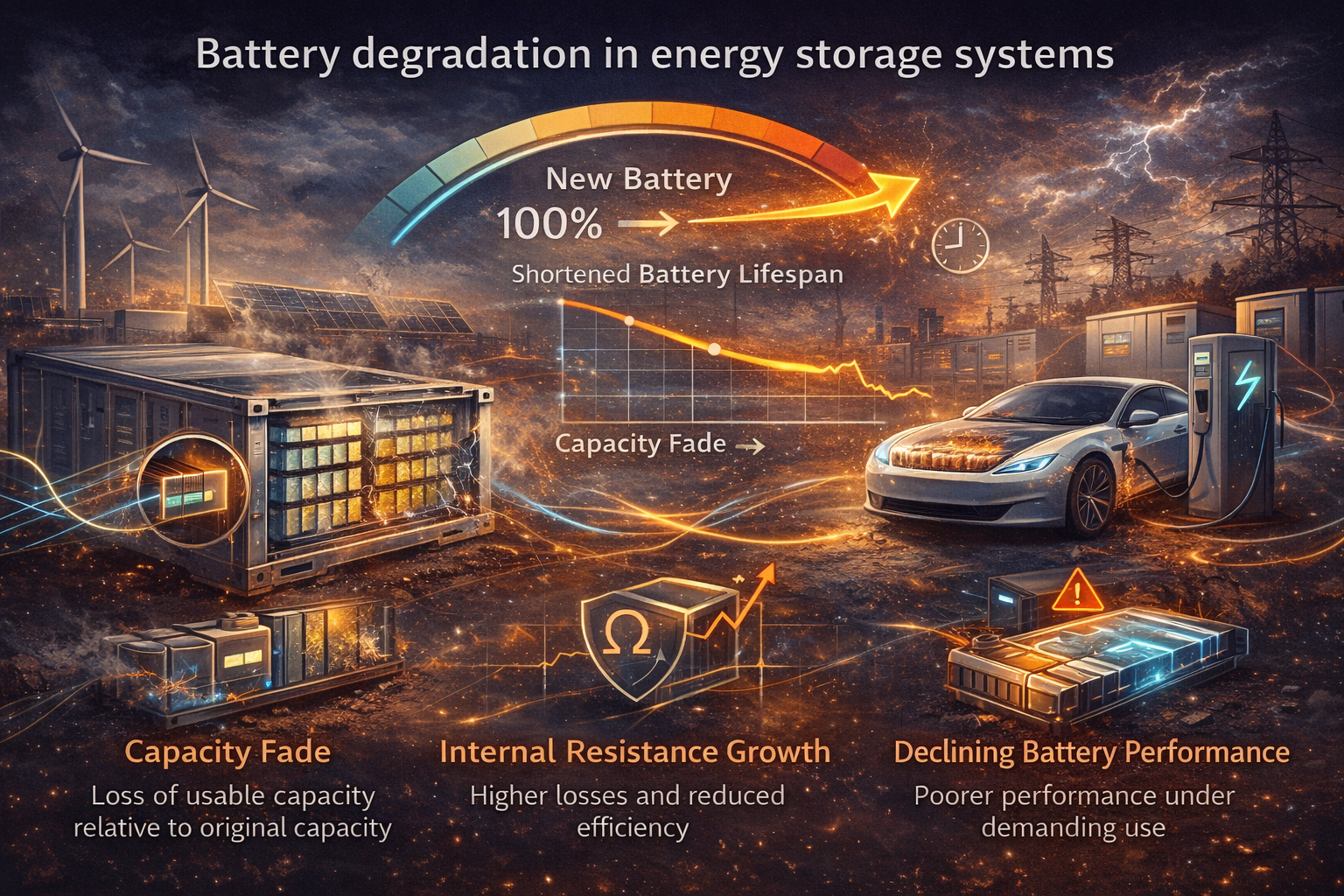

The ESS defines the physical boundaries of the battery storage units: battery storage capacity, thermal limits, efficiency losses, and lifetime degradation cost. You can have modern energy management and the best dispatch algorithms, but the EMS cannot override chemistry, temperature derating, or inverter limits. If the system is constrained, the EMS can only optimise performance inside a smaller operating window, it cannot invent capacity, increase energy density, or ignore safety protections.

That is why seamless integration between the battery racks, modules, and the power conversion system matters. The energy system only works as a bankable asset when hardware is engineered for stability and repeatability. If the ESS has weak thermal design or insufficient PCS capability, the EMS loses degrees of freedom and system performance drops. The ESS is the physical anchor: it decides what the asset can do, how efficiently it can deliver energy, and how quickly it ages under cycling.

Three critical components: EMS, BMS, and the power conversion system

If you want the clean “chicken vs egg” answer, the most accurate model is not EMS vs ESS. It is three critical components acting together:

First, the energy management system (EMS): decides dispatch, market participation, and optimisation.

Second, the battery management system (BMS): enforces battery protection, battery life limits, and safety constraints.

Third, the power conversion system (PCS): converts DC to AC, shapes power output, manages reactive power, and connects the storage system to the power grid.

These key components define the integrated solution. If any of the three fails, the project fails. That is why the EMS is commercially dominant, but never technically absolute.

Who governs money: EMS control of revenue stacking

Most cashflow in battery storage investment comes from multiple revenue streams. Investors want revenue stacking because it reduces dependence on one revenue pool. In practice, the EMS decides how revenue stacking happens: how much capacity stays reserved for ancillary services, how much is used for energy arbitrage, and whether the dispatch can consistently capture market prices without destroying the asset.

The EMS also controls peak shaving behaviour in certain market structures. Peak shaving is not just an industrial behind-the-meter concept: even front of the meter projects effectively do market-based peak shaving by shifting energy into higher-price windows. That is why energy consumption patterns matter. The EMS tracks demand curves, renewable energy generation profiles, and congestion signals to time energy flow.

When markets are competitive, small differences in dispatch accuracy turn into large differences in annual returns. That’s where real time monitoring, data accuracy, and predictive analytics become a profit weapon, not a technical feature.

What risk looks like: why owners and operators can lose different games

In a battery energy storage system, profits and risk are often held by different parties.

The asset owner carries the long-term downside: degradation, battery replacement risk, and battery warranty limits. If the EMS over-optimises short-term revenue, it may accelerate aging and reduce battery life.

The operator or EMS provider can carry operational exposure: penalties for missing grid services, failure to maintain grid stability requirements, or failure to meet performance KPIs.

The integrator can carry contractual risk: disputes about whether system performance issues come from EMS logic, BMS control decisions, PCS constraints, or the battery pack itself.

This is why in real deals, the “who controls cashflows” question becomes a contracting question: who controls dispatch, who takes responsibility for degradation, and who owns optimisation decisions.

Grid operators: why the power grid is the hidden boss

One reason returns vary so much across Europe is grid interactions. Grid operators can impose limits that reduce the EMS optimisation space. Even if your battery energy storage system is technically strong, the grid connection can restrict charge/discharge windows, ramp rates, or reactive power control obligations.

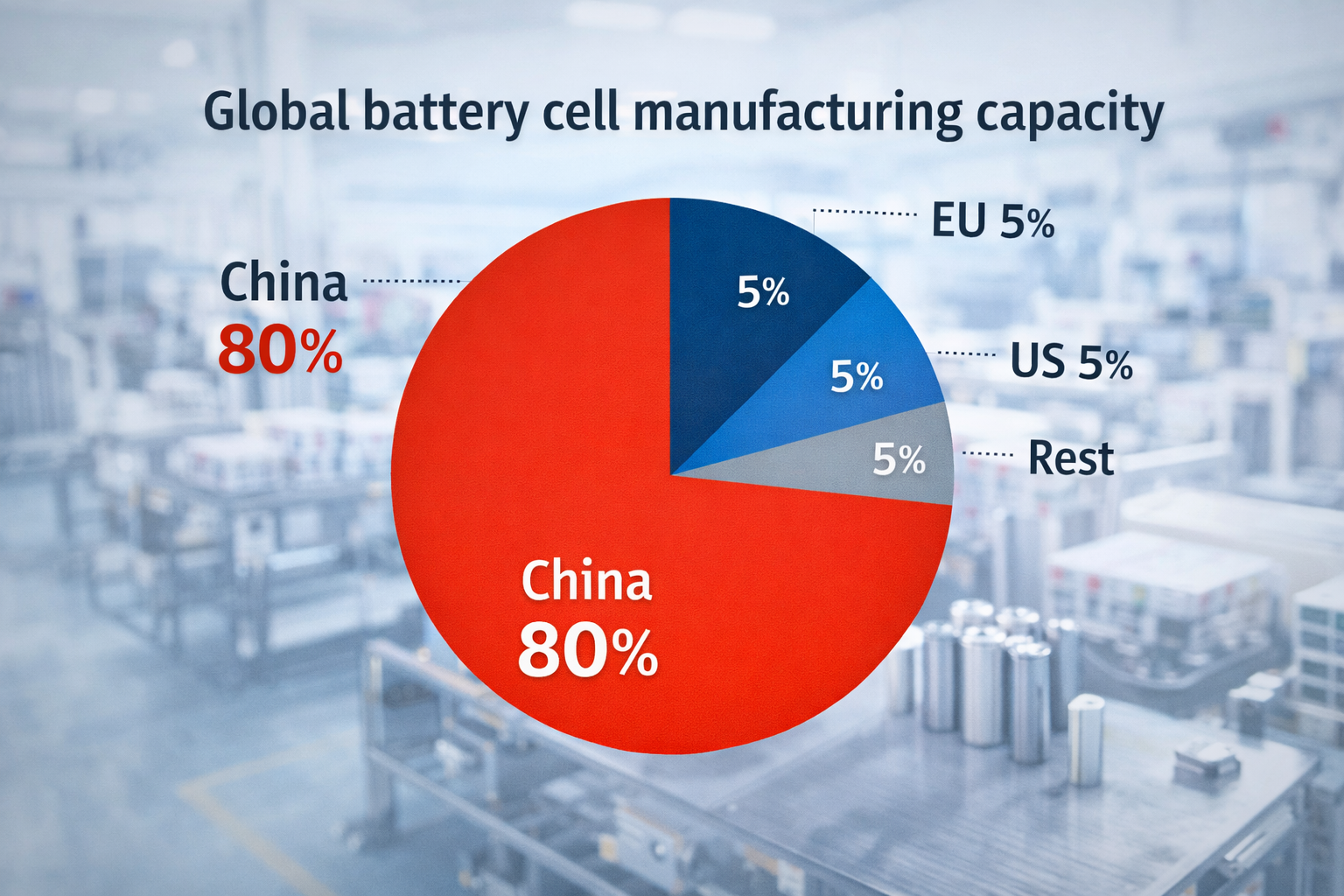

As storage becomes critical infrastructure, expectations rise: maintain grid stability, support grid reliability, and sometimes provide grid services under strict rules. That’s why investors increasingly focus on the grid node, not only the equipment. Location, interconnection rights, and operating permissions often define bankability more than the battery itself.

Behind the meter vs front of the meter: where EMS value looks different

EMS plays differently depending on project type.

In front of the meter projects, EMS value is financial: optimise energy flow, manage market volatility, bid into ancillary services, execute energy arbitrage, and improve power output economics.

In behind the meter projects, EMS value is operational: reduce costs, increase energy efficiency, improve energy reliability, and keep the power system stable for industrial users. For data centers especially, the value is not only wholesale spreads. It is uptime, power quality, and protection from grid instability. That is why behind the meter energy storage is growing as a separate business model.

In both cases, the EMS control system decides how the storage system actually works day to day.

So who rules in the ESS–EMS tandem

If you want the sharp answer:

The EMS controls the money engine.

The ESS controls the failure mode.

EMS controls profits by selecting the best market structures, capturing market prices, and executing revenue stacking through dispatch discipline. ESS controls risk because it is the physical asset that degrades, violates warranty, or derates.

The strongest projects align both: EMS optimisation that improves cost savings and system performance without sacrificing battery life. That requires realistic constraints, not fantasy dispatch.

Conclusion

In a battery energy storage system, EMS is not optional software. It is the control system that decides whether the asset becomes a profit generator or a warranty problem. It governs energy flow, optimizes system performance, and manages participation in ancillary services, energy arbitrage, and grid services using real time data, forecasting, and predictive maintenance signals.

But the ESS remains the physical truth. Battery storage capacity, thermal design, PCS limits, and BMS enforcement define what the system can safely deliver. The future demand trend is clear: higher renewable energy integration, more volatility in power generation, and greater reliance on storage for clean energy stability. That means the winners are the projects built as an integrated solution: seamless integration across key components, high data accuracy, and EMS logic that optimises performance without pushing the asset into risk.

Related Products from Aema ESS

Explore Aema ESS energy storage solutions for backup power, grid support, and renewable energy integration.

Featured systems:

Contact us today to receive a tailored offer for your upcoming project.