For buyers in Northern and Baltic Europe, the choice between two lithium batteries – Lithium-Iron-Phosphate (LFP / LiFePO4) and Nickel-Manganese-Cobalt (NMC) – is not about brand, it’s about physics, temperature limits, and lifetime economics. Both chemistries deliver lithium-ion performance, but their behaviour in cold weather and high-cycle conditions differs sharply. This LiFePO4 vs NMC comparison explains the key differences, unique characteristics, and suitability for different applications, helping you make an informed decision.

Core difference NMC vs LiFePO4

LFP, or lithium iron phosphate battery (LiFePO4), uses an iron-phosphate cathode material. It is chemically stable, operates safely at high temperatures, and tolerates deep cycling with strong thermal stability. The trade-off is lower energy density, meaning more weight and volume for the same kWh. Because LFP batteries are cobalt-free and rely on abundant materials like iron and phosphate, they are typically lower cost and easier to justify in ESG-driven procurement.

NMC, also known as Li-NMC, uses nickel, manganese, and cobalt in the cathode. This chemistry delivers higher energy density and compact size, which is why NMC batteries dominate many electric vehicle and space-constrained applications. However, the stability margin is narrower, and performance becomes more sensitive to high current, high temperature, and cold-weather operating limits. In addition, cobalt and nickel sourcing increases supply-chain exposure and compliance pressure compared to LFP.

Compared to other lithium-ion batteries, both NMC and LFP have clear strengths – but they solve different problems. LiFePO4 is the default choice when safety is non-negotiable, especially for stationary systems like home battery storage.

Battery Chemistry and Composition

Battery chemistry and composition of lithium ion batteries are fundamental to how each battery performs, especially in demanding environments like the Nordics and Baltics. Lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4), commonly called LFP, uses an iron-phosphate cathode material known for chemical stability and reliable performance under frequent cycling. This is why LFP batteries are widely used in stationary storage and other applications where safety and long lifespan matter more than compact size.

NMC (nickel manganese cobalt) batteries use a nickel-, manganese-, and cobalt-based cathode that delivers higher energy density, enabling more energy in a smaller and lighter battery. This makes NMC batteries attractive for space- and weight-constrained applications such as electric vehicles and portable electronics. The trade-off is tighter safety margins and greater sensitivity to thermal management, while cobalt and nickel sourcing can increase cost and environmental compliance pressure. In practice, the best choice depends on balancing energy density, safety requirements, operating temperature, and lifecycle economics

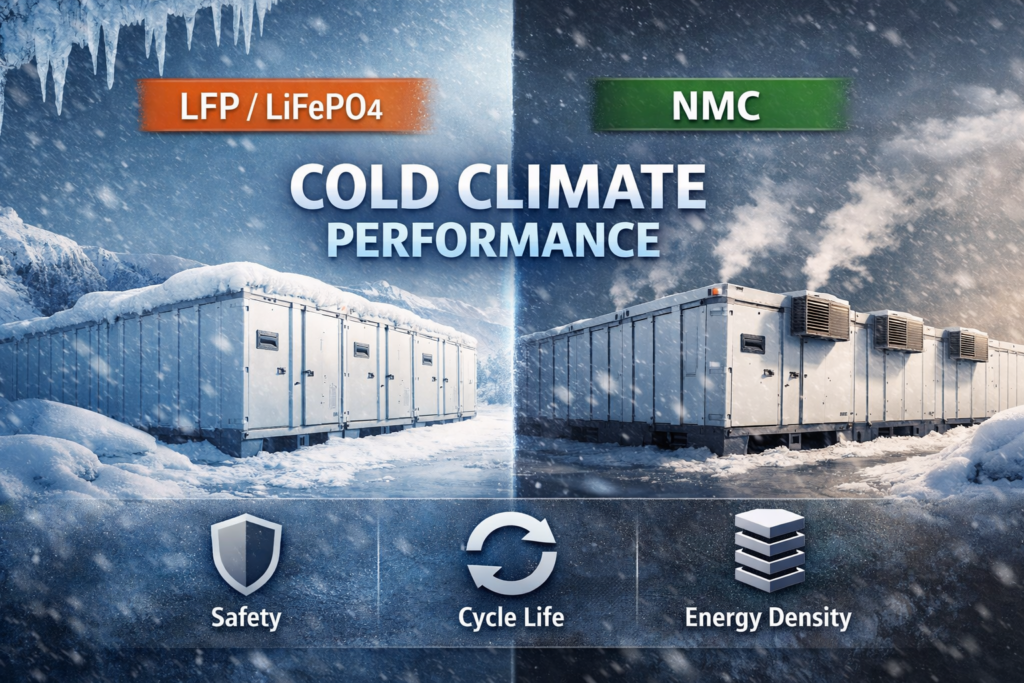

Temperature behavior in the freezing temperatures

In sub zero temperatures, both chemistries lose usable capacity as internal resistance increases. The critical difference is charging. NMC batteries are more sensitive to cold charging and often require stricter current limits and continuous thermal management to reduce lithium plating risk. LiFePO4 batteries are also limited in freezing temperatures and typically need preheating below -10°C, but they are more tolerant of deep cycling and simpler heating strategies. In practice, real performance in the North depends less on the cell chemistry alone and more on insulation, BMS control, and thermal management design.

Safety and thermal stability

Battery safety is a critical factor in battery selection, especially for stationary energy storage systems deployed near buildings or populated areas. LFP (LiFePO4) chemistry is inherently more thermally stable, with a higher thermal runaway threshold (often cited around 270°C). It is more resistant to oxygen release and heat-driven runaway behaviour, which reduces fire-propagation risk under abuse conditions. This is why LiFePO4 batteries are widely preferred for residential energy storage systems and sites where safety and insurance requirements are strict.

NMC provides higher performance and higher energy density, but it demands stricter BMS control, cooling, and protective circuitry, especially when operating at high voltage or in high temperature environments. Compared to LiFePO4 batteries, NMC batteries can enter thermal runaway at a lower temperature (often cited around 210°C) and may release oxygen during failure events, which can ignite the electrolyte and increase fire intensity. This does not mean NMC is unsafe, but it is more volatile and more sensitive to heat buildup, system design, and cell quality if improperly constructed or used. In practice, strong thermal management and protection design are essential to reduce fire risk and ensure safe operation.

For indoor installations and high-exposure sites, insurers and permitting authorities often favour LFP chemistry due to its thermal stability profile.

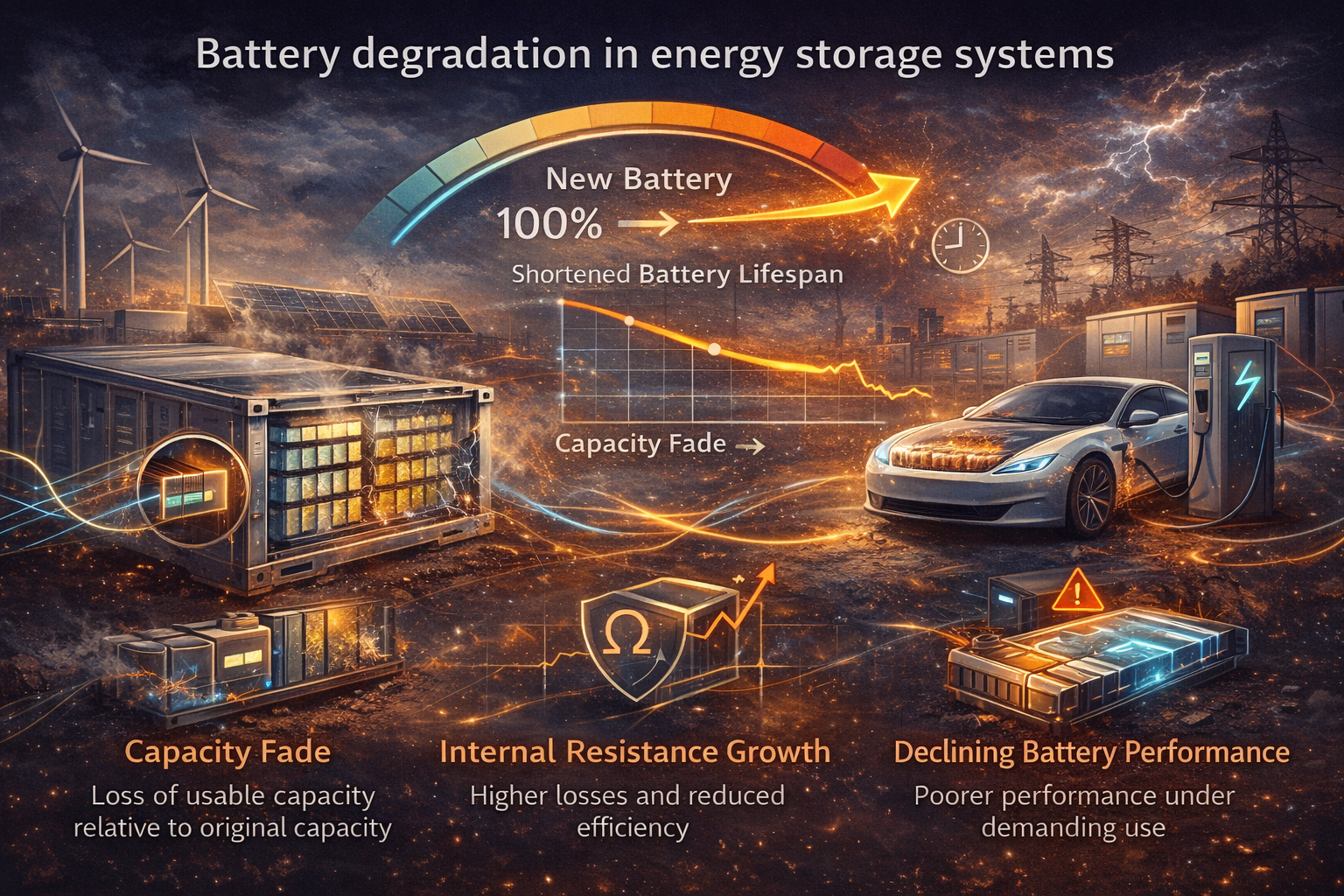

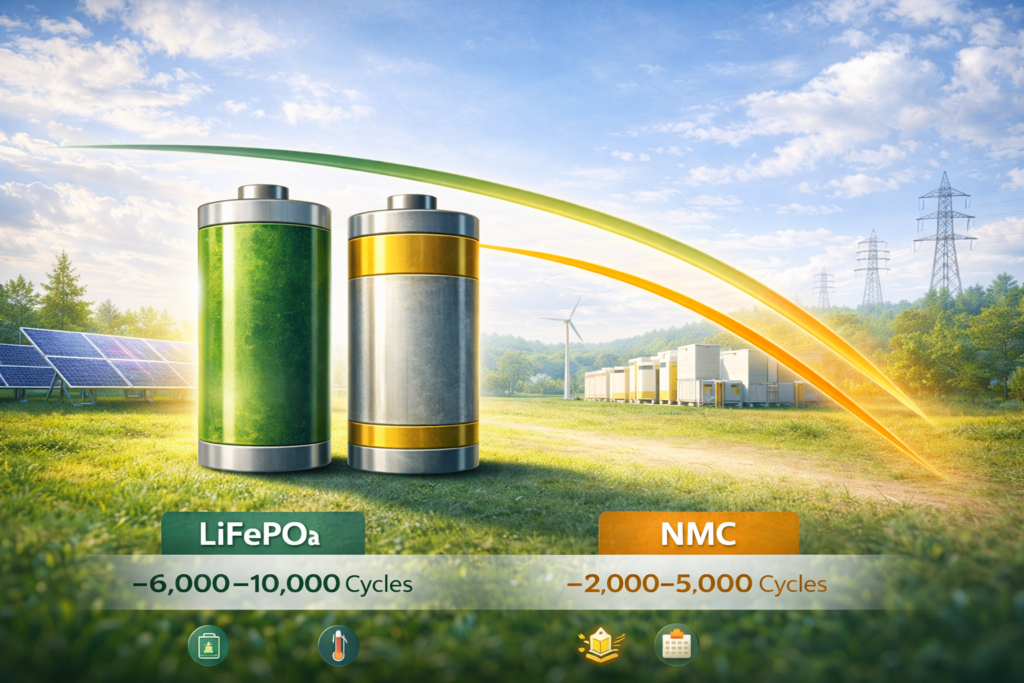

Cycle life and degradation

Battery longevity is often measured in terms of charge cycles and cycle life – how many times a battery can be charged and discharged before performance degrades below a defined limit. In real energy storage projects, degradation is driven by depth of discharge, temperature, C-rate, and calendar aging, not just the chemistry label.

A modern LFP (LiFePO4) cell typically delivers around 6,000–10,000 cycles at ~80% depth of discharge, which makes it attractive for daily cycling and long duration storage. NMC batteries generally deliver lower cycle life under the same conditions (often around 2,000–5,000 cycles, depending on cell design and operating strategy), as degradation accelerates under higher stress and tighter thermal margins.

For storage assets cycling daily, the difference in cycle life can translate into years of additional service life before replacement, which directly improves long-term value. This is why LFP batteries dominate stationary installations such as solar energy storage and backup power systems, while NMC remains competitive in high-power, short-duration markets and space-constrained deployments.

Energy density and footprint

Energy density defines how much energy a battery can store per kilogram (Wh/kg) or per litre (Wh/L), and it directly affects system footprint and weight. In general, NMC cells deliver higher gravimetric energy density, typically around 200–250 Wh/kg, while LFP (LiFePO4) cells are commonly around 90–160 Wh/kg (with newer high-performance LFP designs reaching ~180–200 Wh/kg)..

That density advantage matters when space and weight are constrained – for example in electric vehicles, portable electronics, marine systems, or rooftop installations. For the same energy capacity, LFP-based systems typically require more volume and heavier racks, while NMC can deliver the same kWh in a smaller, more compact size.

For most ground-mounted energy storage in the Baltics and Scandinavia, the footprint penalty is usually manageable. In these markets, cold-weather reliability, safety, and thermal management often matter more than maximum energy density.

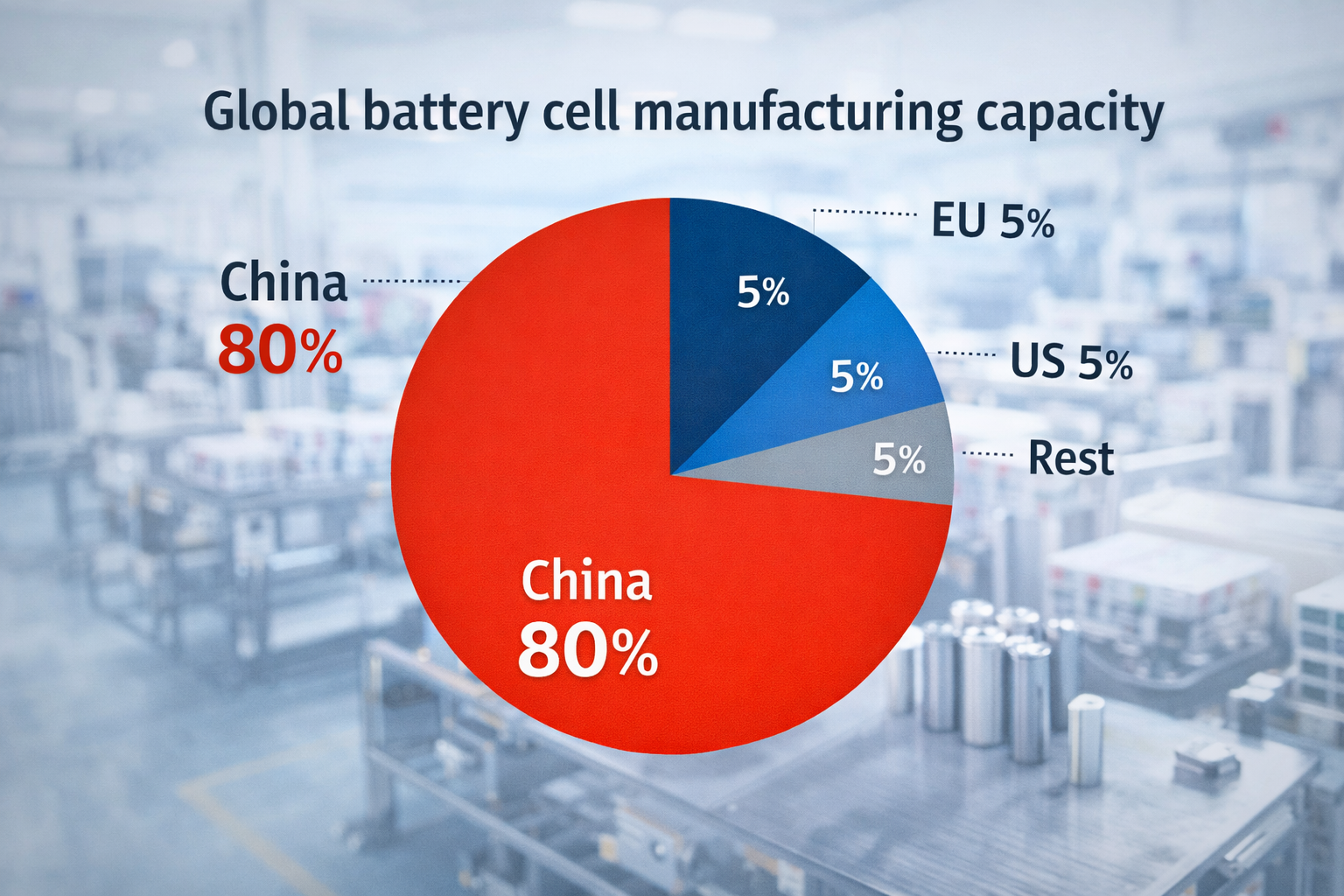

Environmental and compliance factors

Under the EU Battery Regulation (EU) 2023/1542, battery supply chains face stricter requirements for transparency, due diligence, traceability, and end-of-life obligations. Chemistries that rely on cobalt and nickel typically carry higher compliance and reporting pressure, especially around responsible sourcing and recycling.

LFP’s iron-phosphate chemistry is cobalt-free and generally simplifies sourcing risk and end-of-life handling compared to nickel- and cobalt-heavy cathodes.

In ESG audits, this often translates into a lower declared CO₂ footprint per kWh installed and fewer supply-chain red flags, especially for buyers prioritizing sustainability documentation.

Battery Management System

A Battery Management System (BMS) is the control and protection layer of any modern lithium-ion battery pack. It continuously monitors voltage, current, temperature, and state of charge, and enforces safety limits to prevent overcharging, over-discharging, overheating, and cell imbalance. In real projects, BMS settings directly influence usable capacity, performance, and warranty compliance.

For LiFePO4 (LFP) systems, the BMS is critical for managing cold-weather charging limits, balancing, and long-term health tracking. For NMC batteries, the BMS plays an even stricter safety role due to higher energy density and tighter thermal stability margins, requiring more aggressive control of voltage windows and thermal protection. In both chemistries, a well-designed BMS is essential to maximise safety, energy output, and battery lifespan.

Real performance in the North

Field experience from Nordic and Baltic deployments suggests that well-managed LFP systems can retain close to nominal performance through winter operation when supported by moderate preheating and controlled operating windows. Comparable NMC systems often require tighter insulation and continuous active thermal regulation to avoid cold-related degradation mechanisms and power derating. In cold climates, the auxiliary energy used for constant heating can partially offset the energy density advantage of NMC at the system level.

Applications and Use Cases

Lithium-ion batteries, including LiFePO4 (LFP) and NMC, power everything from electric vehicles and consumer electronics to utility-scale energy storage. In practice, the right chemistry depends on application demands: energy density and compact size versus safety, cycle life, and long-term durability. For buyers in the Nordics and Baltics, cold-weather operation often becomes the deciding factor.

Automotive and Industrial Applications

In the automotive world, NMC batteries are widely used in electric vehicles thanks to their high energy density and compact size, enabling longer driving ranges and more efficient use of space. This makes NMC the go-to choice for passenger cars and high-performance vehicles where maximizing energy in the smallest space is a clear advantage. However, LiFePO4 (LFP) batteries are increasingly adopted in electric buses, trucks, and other heavy-duty vehicles where safety, thermal stability, and a longer lifespan matter more than squeezing out the highest possible energy density. In industrial settings, LFP batteries are valued for resistance to overheating and reliable performance in demanding high-temperature environments, where safety and durability are paramount.

Renewable Energy Storage

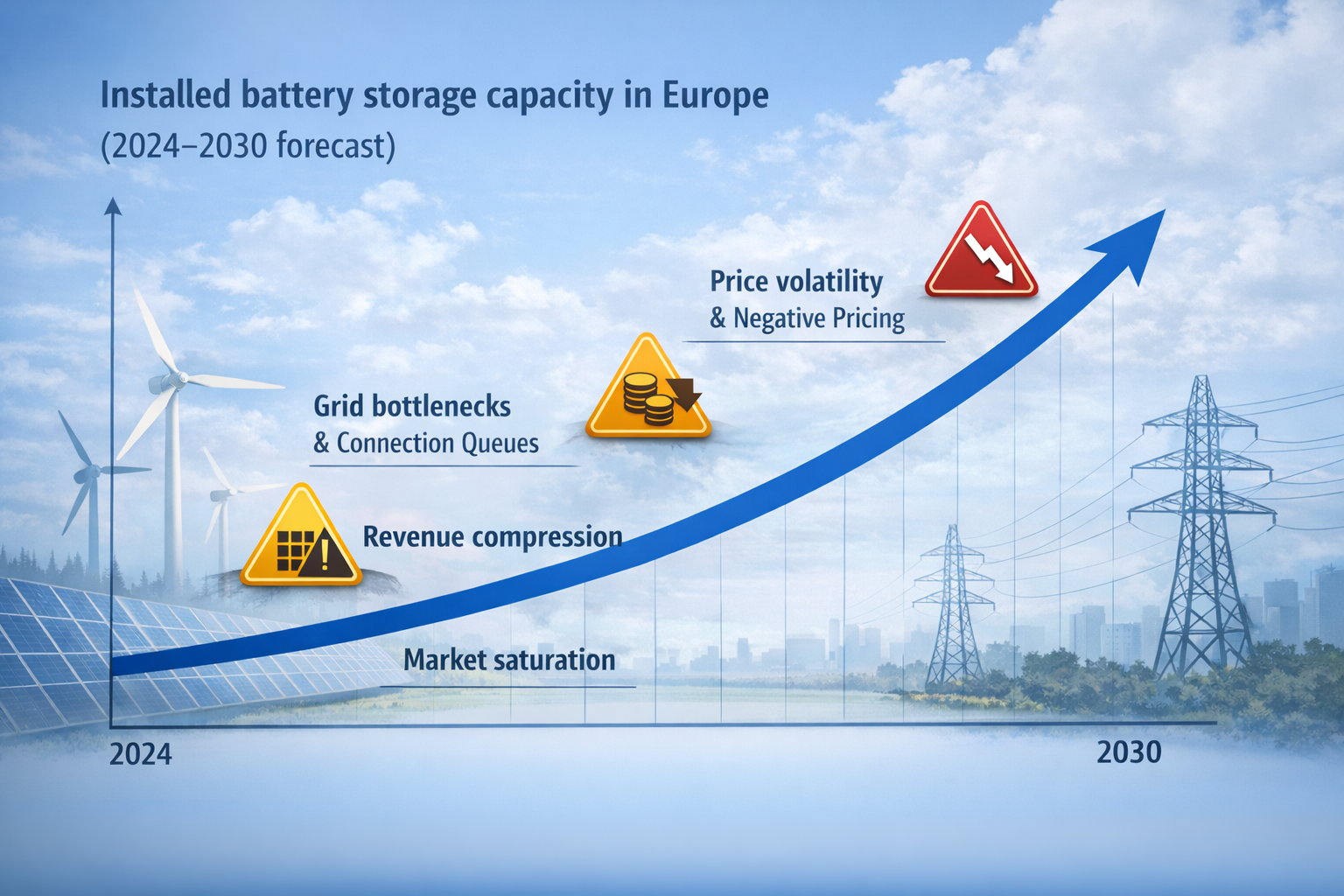

For renewable energy storage, such as solar and wind systems, LiFePO4 batteries have become the preferred option due to their long cycle life, high thermal stability, and eco-friendly, cobalt-free chemistry. These batteries can handle frequent charge and discharge cycles without significant degradation, making them ideal for daily use in solar systems and other renewable installations. While NMC batteries offer higher energy density, they often require more sophisticated thermal management to operate safely in environments with fluctuating or high temperatures. Recent advancements in NMC technology have improved their thermal stability, making them a viable choice for certain renewable energy projects, but LFP batteries continue to lead in applications where longevity, safety, and environmental impact are top priorities.

Market trend

By 2024, LFP (LiFePO4) became the dominant chemistry in European stationary storage for projects above 1 MWh, driven by safety, cost, and long-term cycling economics.

NMC remains strong in electric vehicles and space-constrained hybrid systems, but in cold-climate stationary storage the market continues shifting toward LFP for lower risk and more stable lifetime performance.

Conclusion

NMC wins on energy density and fast response, while LFP (LiFePO4) wins on stability, cost, and endurance. In Northern and Baltic Europe, where temperature limits, insurance requirements, and long-term operation matter more than compactness, LFP is often the practical and economic choice for stationary energy storage systems. It is safer to own, cheaper to maintain, and easier to certify under EU standards. For buyers focused on commercial reliability rather than laboratory energy density, LiFePO4 vs NMC is a simple decision: LFP is the chemistry that consistently works.

Related Products from Aema ESS

Explore Aema ESS energy storage solutions for backup power, grid support, and renewable energy integration.

Featured systems:

Contact us today to receive a tailored offer for your upcoming project.